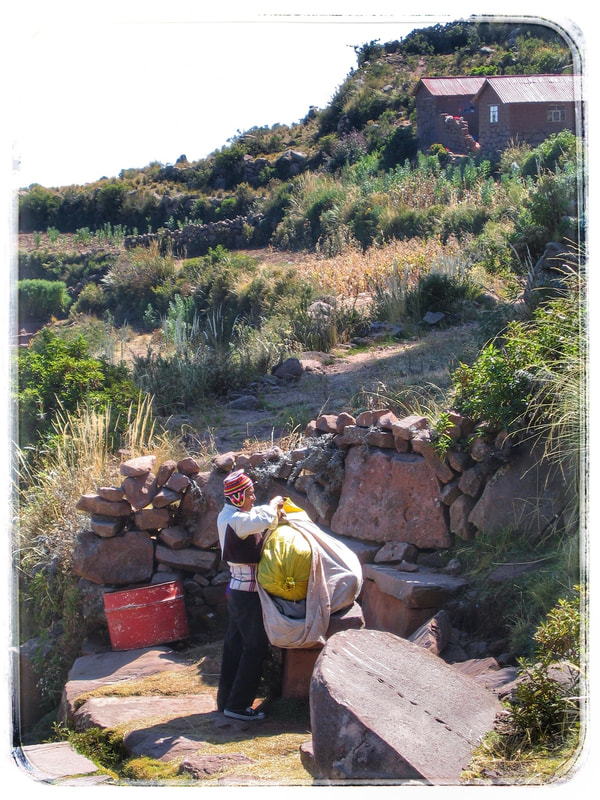

After breakfast, we boarded our bus and headed off to see another Temple of the Sun. This time at Sillustani. Enroute we passed small clusters of homes and farms, all made of stone — the homes, walled gardens and livestock enclosures.

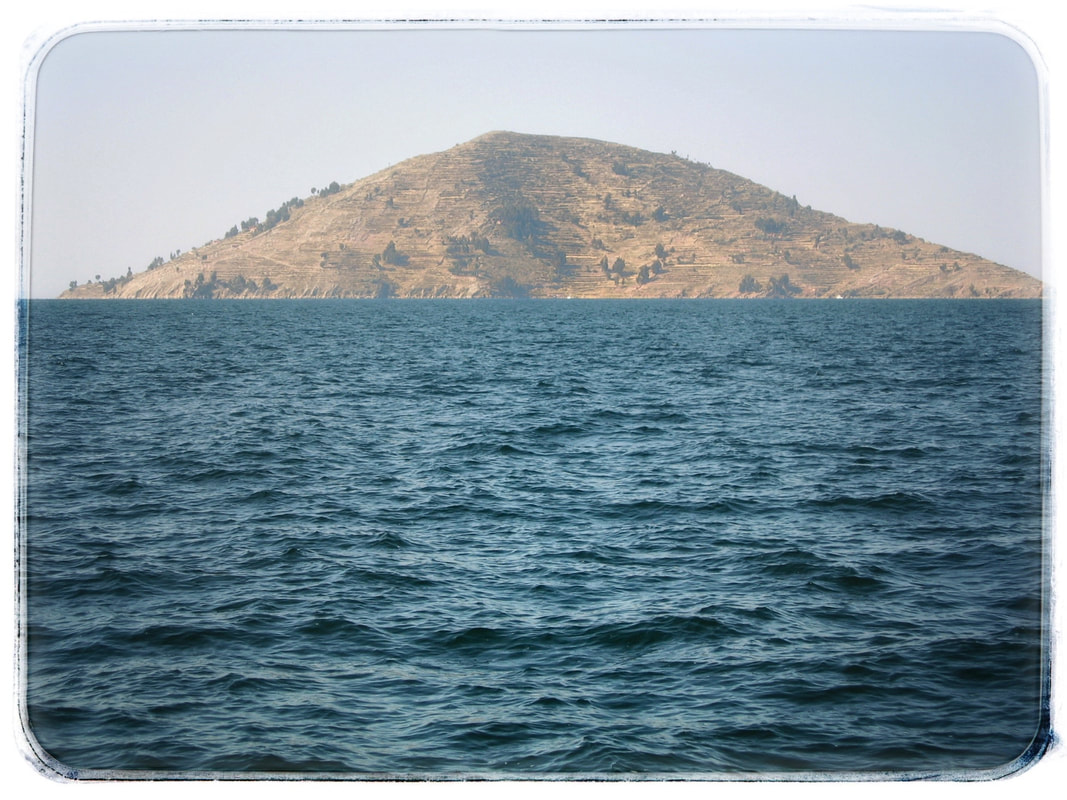

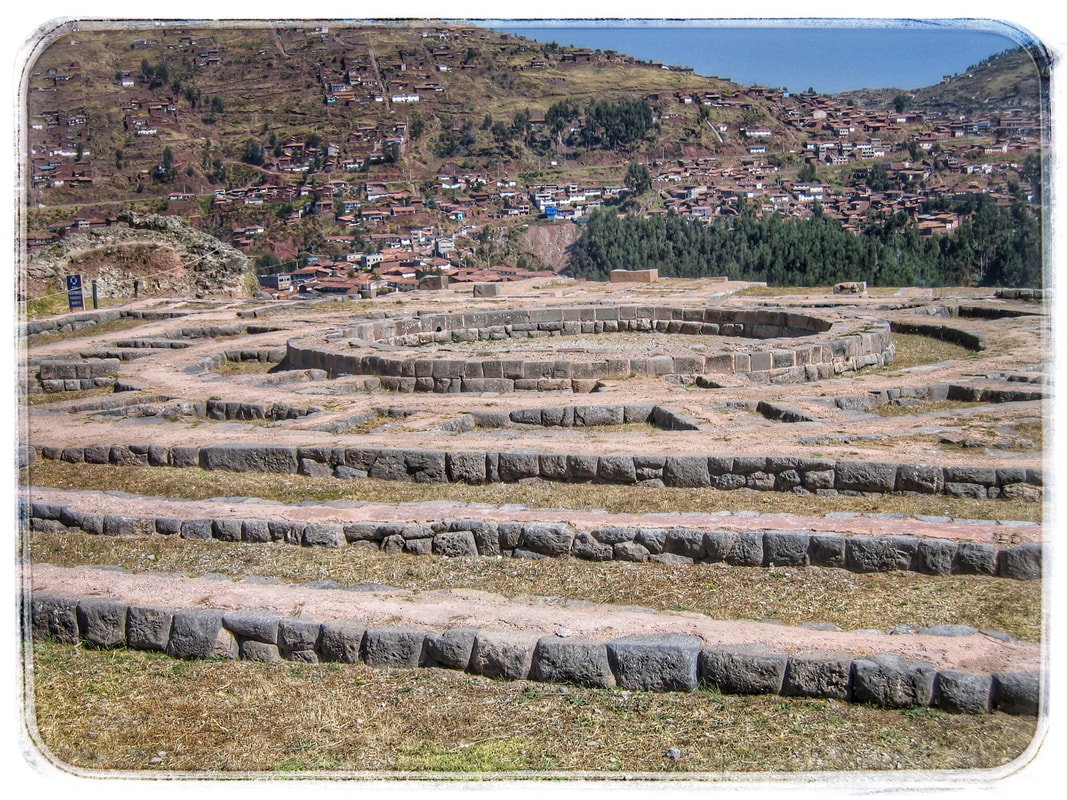

- Sillustani is built on a plateau above Lake Umayo, which means “headwaters.”

- There is evidence that at one time, Lake Umayo connected to Lake Titicaca.

- Curiously, guinea pigs were used to scan the human body for ailments, not unlike an x-ray machine, and some Andean medicine people still practice this diagnostic method.

|

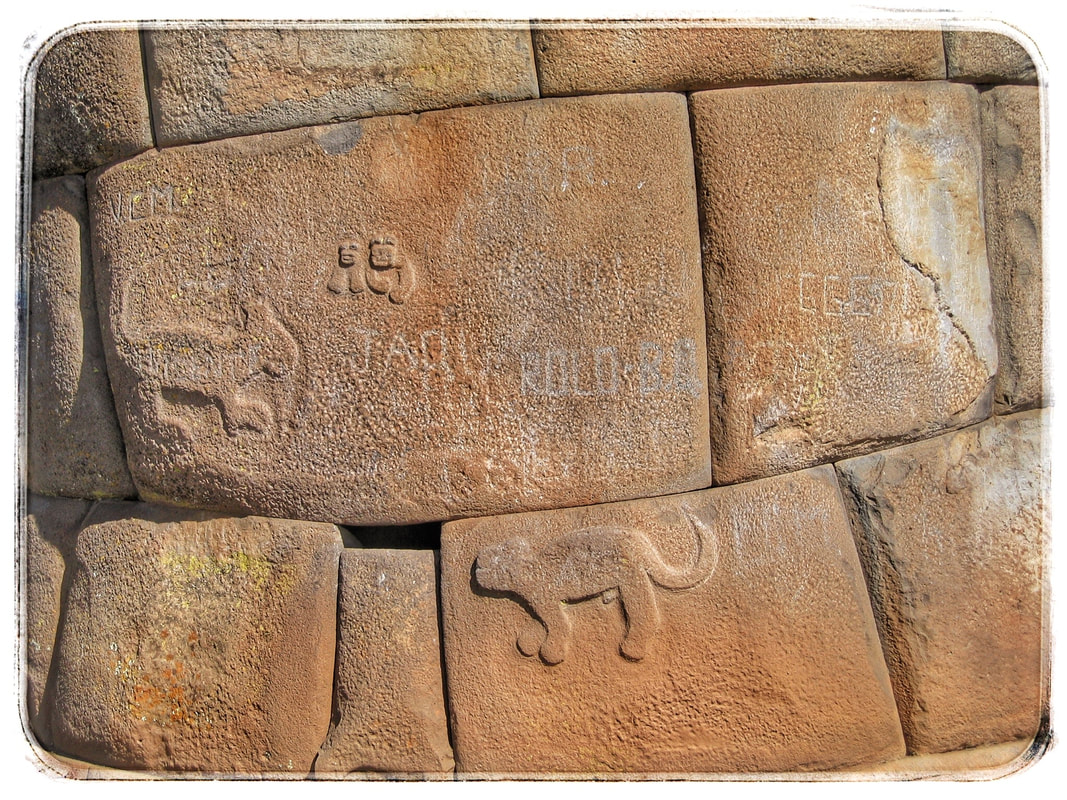

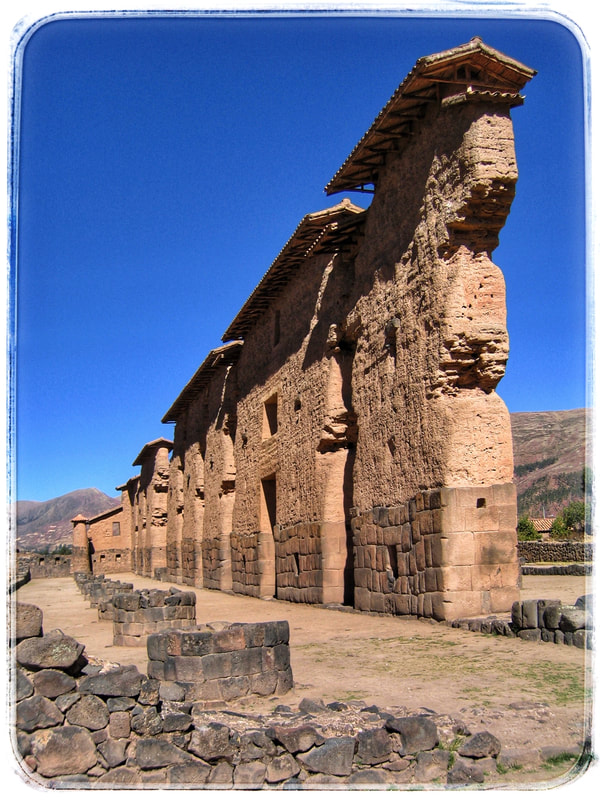

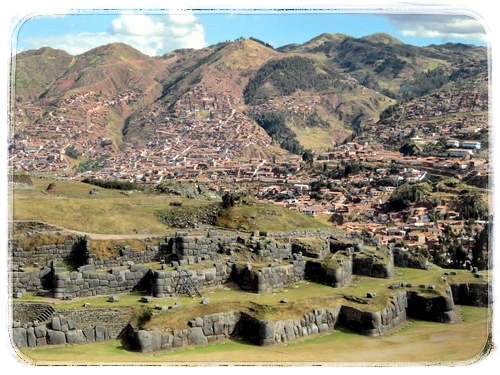

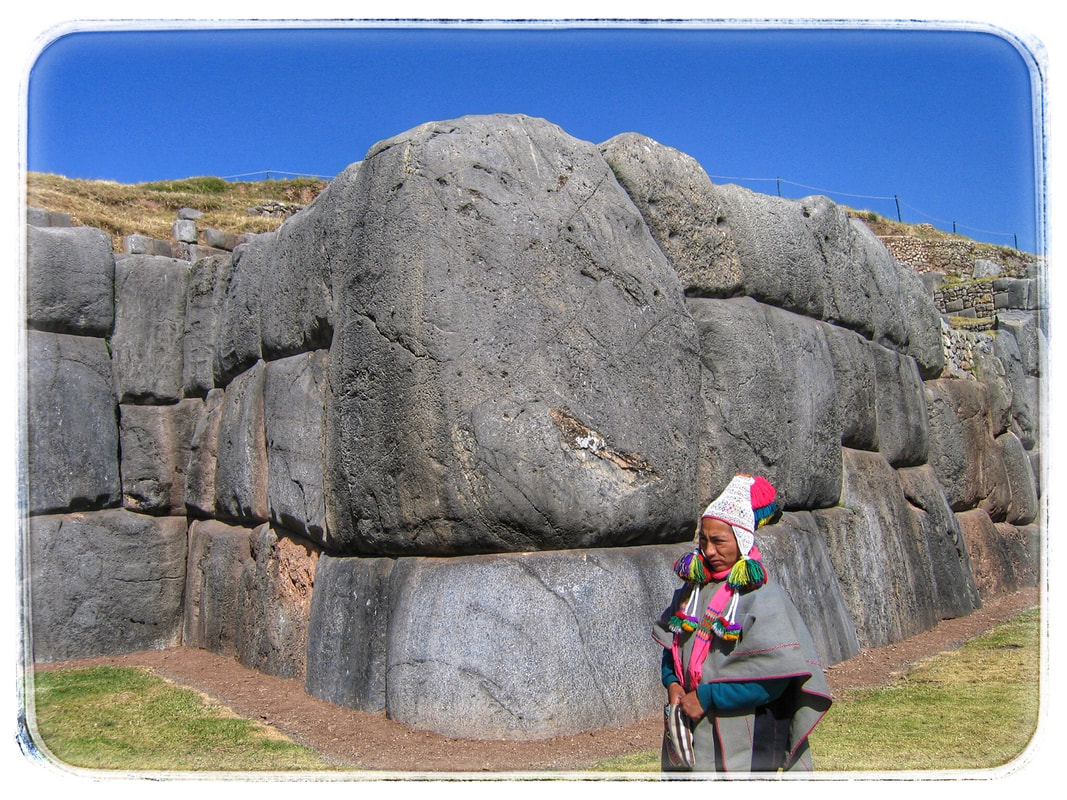

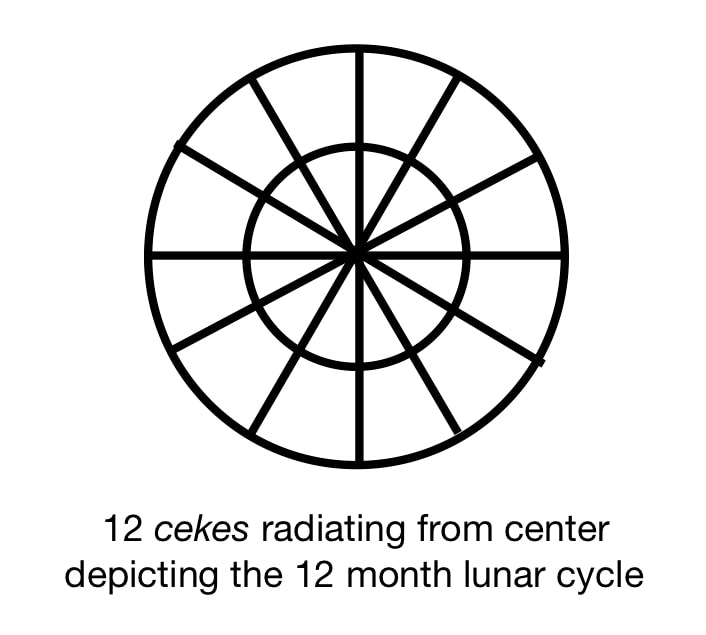

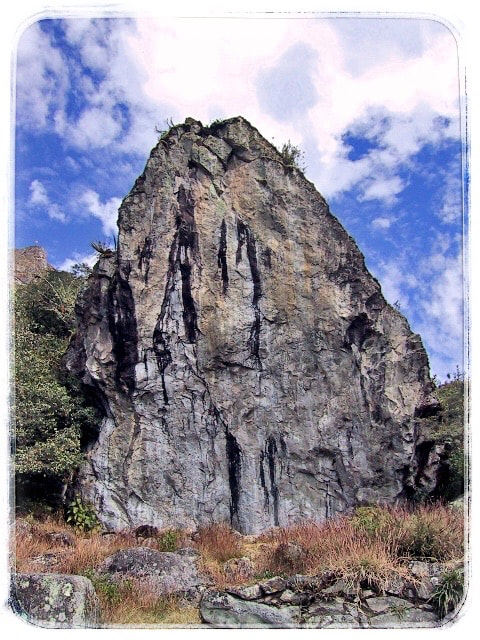

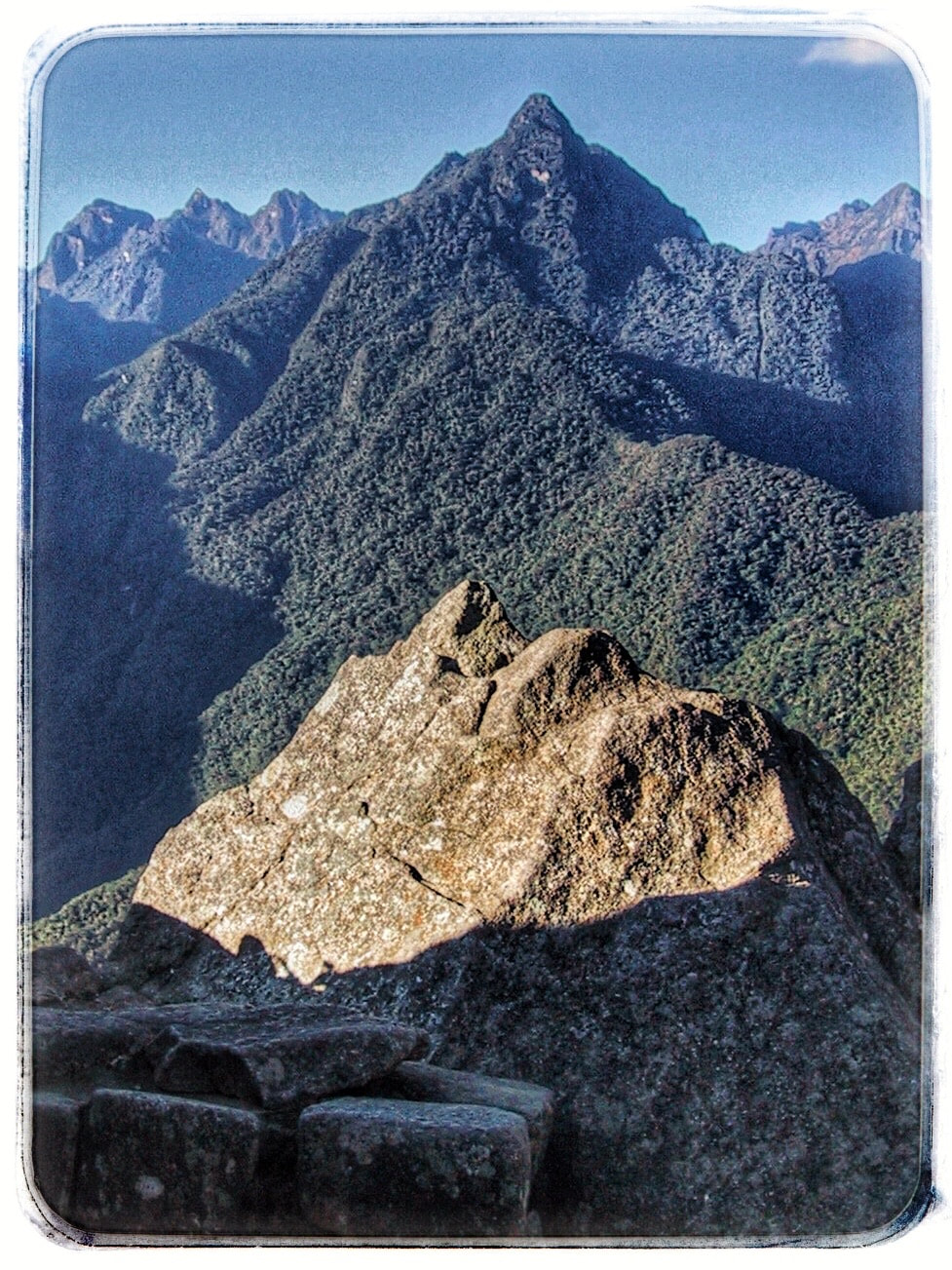

| We learn, too, that archeologists found stone representations of the Southern Cross (symbol of the Inka Cross) and one of the most sophisticated celestial dials in the center of the Temple. The dial was a stone huanka, which are large stone monoliths that represent fertility, and were erected to provide an anchor point (coordinate) to the ongoing creative processes of life. The celestial dial huanka had four notches that would have held vertical rods that related to specific points in the night sky used to determine celestial coordinates. Four constellations, in particular, show up longer within this matrix longer than others: Fox, Southern Cross, Llama (Alpha and Beta Centauri) and Snake. |

| All of the other stones in the ruin are in radial relationship to other celestial bodies. In fact, it has been found that the Temple is almost an exact approximation of where those four celestial bodies would have been 2800 years ago during the Age of Taurus. During that span of time, the earth has experienced a 23% wobble, many great earthquakes, floods. There is even evidence of a great flood at Sillustani, and stories about a white paqo (medicine man) who was messiah-like and had a white llama. |

| Besides being a sacred place to bury the dead, Sillustani is also a place to honor one’s ancestors through symbols such as huankas. Standing at this one, facing northwest towards Lake Titicaca, I sent prayers to my ancestors and close relations who have made their great crossing, and as I did so, felt energy surge through my body. |

Shamans know that huankas speak to them, so it is vital that a shaman has a huanka at the primary place from which they source, generally at their home. Shaman connect through kollana cekes to their personal huanka, which serves like a backup storage devise for their relationships and engagements. In this way they never feel abandoned.

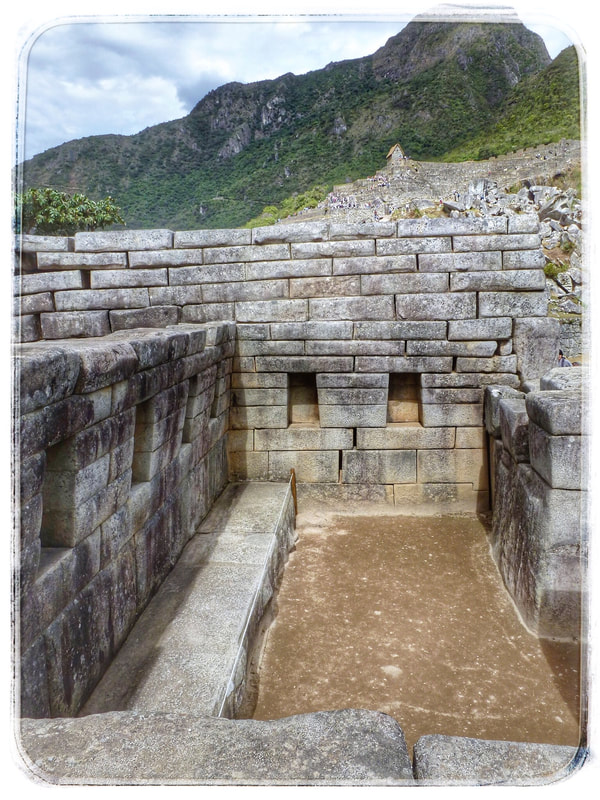

After taking group photos above the lake, a closing ceremony was held nearby in a square-shaped stone enclosure. Here we fed each other k’intus with our prayers. Then, holding hands in a circle, took turns thanking Pachamama, the apus, all of the celestial beings, elementals, Jose Luis, and each other for showing up for this extraordinary journey.

After a five+ hour wait, I boarded my flight to Los Angeles around 1AM. Exhausted and needing to begin process all that I'd experienced, I slept through most of the flight. The line through US Immigration and Customs went quickly, and after dropping off my luggage for a connecting flight to Santa Barbara Airport, walked the United terminal. By late morning Rick and our two Boxer boys were waiting to welcome me home!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed